Major and Minor Chords and their Progressions

This article will teach you how to write beautiful sounding chord progressions.

For the best experience, listen with headphones.

A chord is simply a collection of 3 or more tones. Any collection of 3 notes is a chord. The connection of chords is what creates harmonic tension.

As we remember from looking at the physics of sound and by examining the intervals, certain tone combinations are more consonant and harmonious than others. We've already done much of the heavy lifting!

Based on the natural overtone series, we know that the most harmonious new tones that go together with a fundamental tone is its fifth and third.

A triad consists of a root with the fifth and third.

You can form a triad on top of any note by considering that note a root, and then building a chord by adding the third and fifth above it.

Figure 1. Each triad is composed of a root with its perfect fifth and third.

The main thing to remember is that the fifth above the root must be a perfect fifth. A reminder: the interval of B-F is a tritone, so that fifth needs to be B-F# or Bb-F.

Major and Minor Triads

So the fifths in triads are always perfect, with a few exceptions as we'll soon see. But remember that thirds are not perfect—there are 2 qualities of thirds: major and minor. A triad with a major third above the root is a major triad. Similarly, a minor triad has a minor third above the root. The fifths above the root are always perfect.

Figure 2. When labeling triads with the note names, use upper case for Major and lower case for minor.

The name of the triad is given by the root. For example, the root of a C major triad is C. The recipe for building a triad is: "root-third-perfect fifth".

Try building some triads: B major, b minor, Eb major, c minor.

Answers: B-D#-F#, B-D-F#, Eb-G-Bb, C-Eb-G.

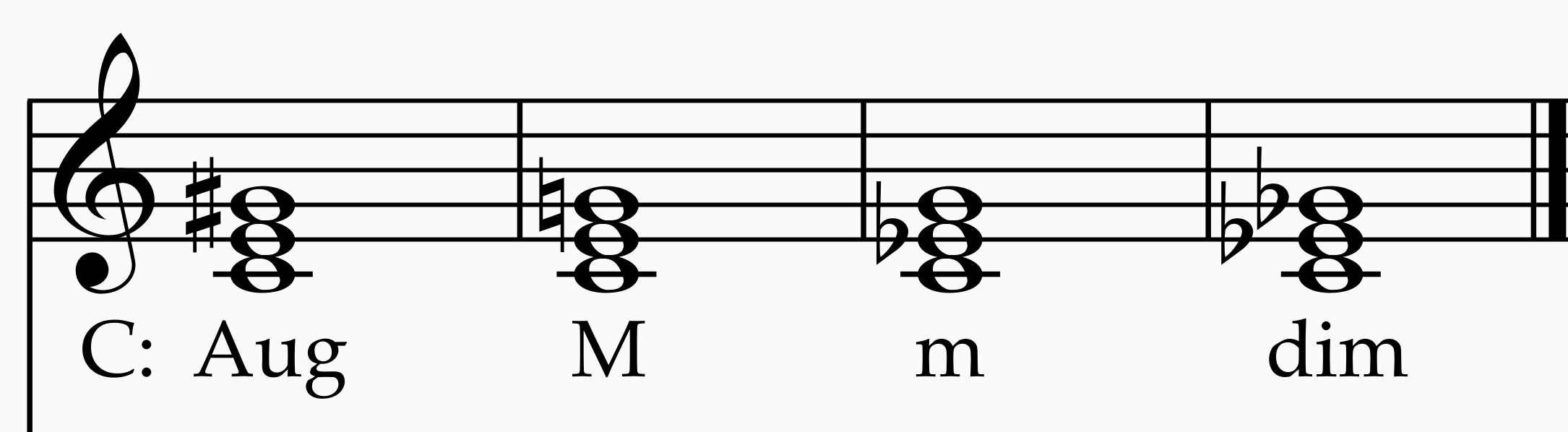

Augmented and Diminished Fifths

We've just seen 2 forms of the same triad that differ by lowering or raising the same pitch, the third, by a half step. We can do the same with with the perfect fifths, although they will no longer be perfect, sadly. Raising a perfect fifth by a half step makes it larger, or augmented. Conversely, lowering a perfect fifth by a half step makes it smaller, or diminished. Triads with the same root come in 4 varieties then as shown by Figure 3. The last 3 are the most common; augmented triads are used later in history and belong to the realm of chromatic harmony.

Figure 3. An augmented fifth is enharmonically equivalent to a minor sixth, and a diminished fifth is enharmonically equivalent to a tritone.

How are chords organized?

We've seen through the study of the intervals that the musical effects only take place within us when we live the connection between two entities. It is the same with chords.

In the case with tonal harmony the chords are organized by the musical scale.

The notes of the musical scale have names and their names actually describe the connections between it and the root or tonic of the scale!

Figure 4: The names of the notes. Numbers are the degree of the scale. Italics show the Solfege syllable.

Let's look at the major scale. Again, the name (tonic, supertonic, etc) refers to the connection of the scale note and the tonic of the scale that it belongs to. The name "subtonic" makes no sense without being in relation to the tonic, and the same is true for each note name.

Remarkably we can understand the connection, the meaning of the names, by studying the interval itself. For example, the dominant can be studied by experiencing the perfect fifth up, or a fourth down. The submediant can be experienced by singing a major sixth up, or a minor third down. Just like we did with the intervals.

These names actually represent the connection, so dominant means harmony built above the fifth scale degree of the tonic. Mediant means harmony built above the third scale degree.

The harmony itself is built as a triad above each scale degree. Another way of saying this is the harmony is built with thirds above each scale degree as the root of the triad using the other notes of the scale. For example, the triad above D is not D-F#-A but rather D-F-A because those tones are in the C major scale.

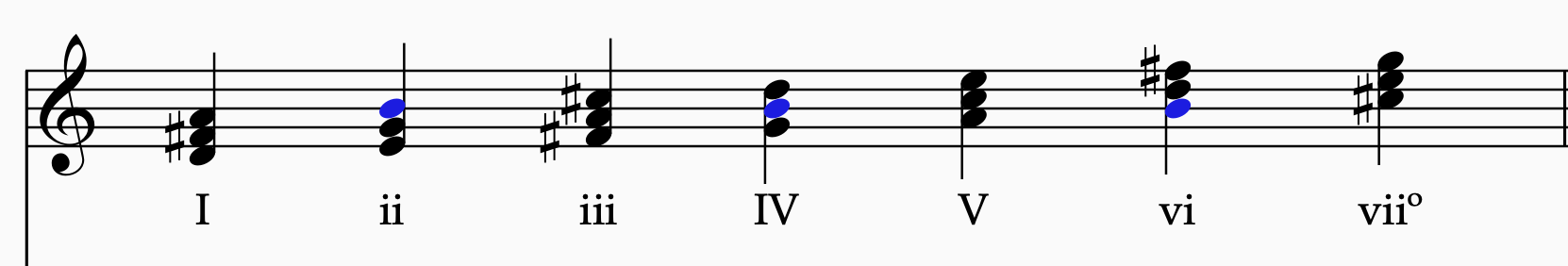

Figure 5: The Roman numeral represents the name and corresponds to the scale degree as in Figure 4, but now it also represents the chord quality. Upper case numerals represent major triad, and the lowercase numerals represent a minor triad. The major and minor thirds are determined by the notes in the C major scale itself. The circle next to the vii represents a diminished triad. The fifth is diminished because F# is not in the C major scale.

What is the difference between a chord and a triad? A triad is a chord, but a chord is not necessarily a triad. That is to say, a triad is a specific type of chord built from thirds above the root. But there are plenty of other non-triadic chords, especially since we defined them as any collection of 3 or more simultaneously sounding tones.

As you can see in Figure 5, each triad is built with the notes of the scale. This is also to say that the triads are in the key of the tonic.

The plan now is to first learn how we connect the triads, and then we will learn the meaning of each chord name by experiencing them to find out how they function.

The Connection of the Triads

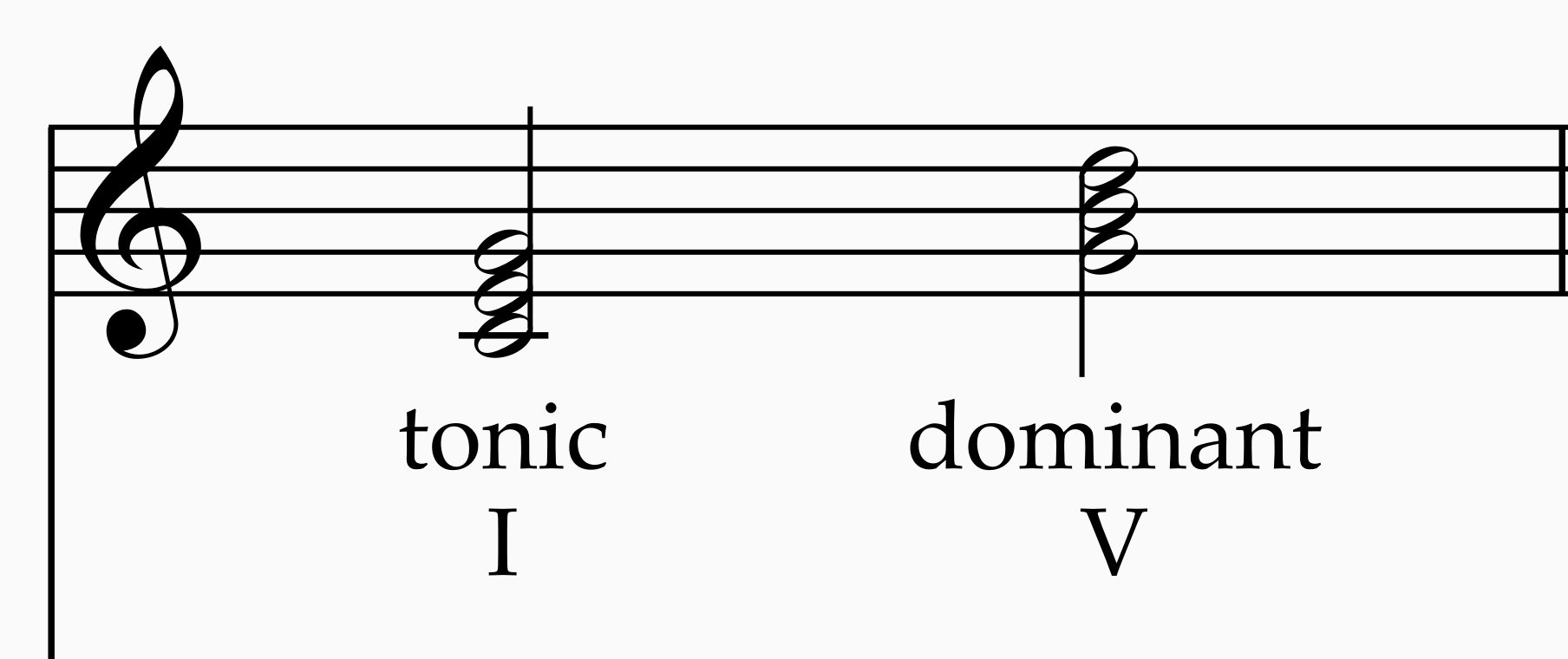

First a quick detour to cover some basic part writing directions. If we want to play the connection between tonic and dominant for the purpose of experiencing how the connection feels, then you could just play them as they appear organized by the scale.

Figure 6.

As you can see and hear, it's not very smooth.

This brings us to our next chord feature.

Chords can be inverted.

Triads can be inverted by raising the bottom note up by an octave.

Figure 7. Each tone is raised just one octave. When the root is the bottom most note in a triad then it is said to be in root position. The structure of the first and second inversions are shown here.

To smooth out our chord connection from Figure 6, we can use the same triad in another inversion to keep the common tone (G) in the same voice, and make horizontally moving intervals as smooth as possible.

Figure 8. The tonic chord is in root position and the dominant chord is in first inversion. That's some smooth voicing.

Chords can also be in the open position.

Figure 9. We are open for business.

The open position of the triad is made by raising a middle voice up an octave. This also creates a very different sound. Let's now connect tonic and mediant with 4 voices in the open position.

Figure 10. Always try to find the common tones between connecting chords and sustain them, which means keep them in the same voice that they are in. The voices are referred to as Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Bass (from top to bottom), usually abbreviated as SATB.

This art of connecting chords has been practiced for at least 500 years, and extends all the way back to the vocal music in European churches. That's why we study the 4 'voices.' But what is the purpose of studying music this way, especially if we wish to create contemporary music that breaks tradition? I would say that this approach is in touch with a very human way of working with the tones, and does so in a way that respects their nature. Composers from Balada to Stravinsky, Brahms, and Beethoven all studied the tones in this way, and each of them has created an influence of the sound of our music today. Learning this method is to learn the method of the greatest musicians. On connecting the triads, Anton Bruckner called it "the law of the shortest way."

Directions for writing chord connections.

1. Keep the root in the bass (for now).

2. Sustain the common tones.

3. Fill in the remaining tones with the middle voices, obeying the law of the shortest way.

Chord Functions

As we have just learned, the names of the triads describe the connection they have to the tonic. The connection is both in interval and in feeling. After working with chords for a while, the term submediant goes from a noun to mean "a triad built on top of the 6th scale degree" to more of an adjective that describes a feeling. Training your ears this way will let you hear and feel that a chord in a large progression has a "submediant" quality to it, or a "dominant" quality to it. Once you develop this feeling, then you can compose and build structures that express these "inner" qualities of the chord connections. With chord functions and functional harmony, we seek to understand the material with the intention of using it to compose or understand how a composition works. Here we will rework the theory to make it more useful to our understanding as musicians developing a living relation with sound.

Figure 11. Moving from stability to instability. This series arranges the chords not based on their natural order in the scale but instead based on how close or far away the root is according to its overtone relation to the tonic. Remember back to the lesson on the intervals where Paul Hindemith arranges them from more consonant to more dissonant—"series 2", bringing it back to the laws of nature. Here the scale-triads of figure 5 are rearranged (and repositioned) to show their tonal significance. Chords that are closer to the tonic are more strongly charged to the tonic, and tones that are further away are less stable and more tonally ambiguous.

Some perspective on how to use these diagrams (figures 11 and 11.5) for understanding harmony.

You can think of the tonic as a center of gravity, and all of the notes here are arranged like planets in a solar system. (The scale does not arrange the notes in this way). If you are in C major and only play chords that are close to the tonic in this series, such as the V or IV or vi, then you are going to stay very “close” to that tonal center of C major. However, if you want to leave C major or are approaching C major from somewhere else, then you can approach from outside of the solar system. In this case, a D minor or an E minor chord would be the first stable sound when approaching the key of C major from another key. You can then play chords that move closer and closer to the stable gravity of C major, moving in the right to left direction in the series. This understanding is useful and important for when we start turning one tonal center into another.

Feeling what the chord names mean.

Figure 11.5. (Treble clef not shown). How to experience the connection of the triads. Observe the common tones as you move from left to right in this series. The tonic and dominant share the G, the closest and strongest note to C in C major, and the supertonic and subtonic triads share 0 tones in common with the tonic triad. Again, this series improves organizing the diatonic (relating to the scale) triads by placing the chords according to their importance in stabilizing the tonic. As you’ll see, each chord has either a dominant, predominant, or tonic function given by their sound.

Listen to Figure 11.5 where I play each chord very slowly to get the sense of how each chord feels when moving from the tonic. Again, this practice teaches you what the chords mean and how to use them.

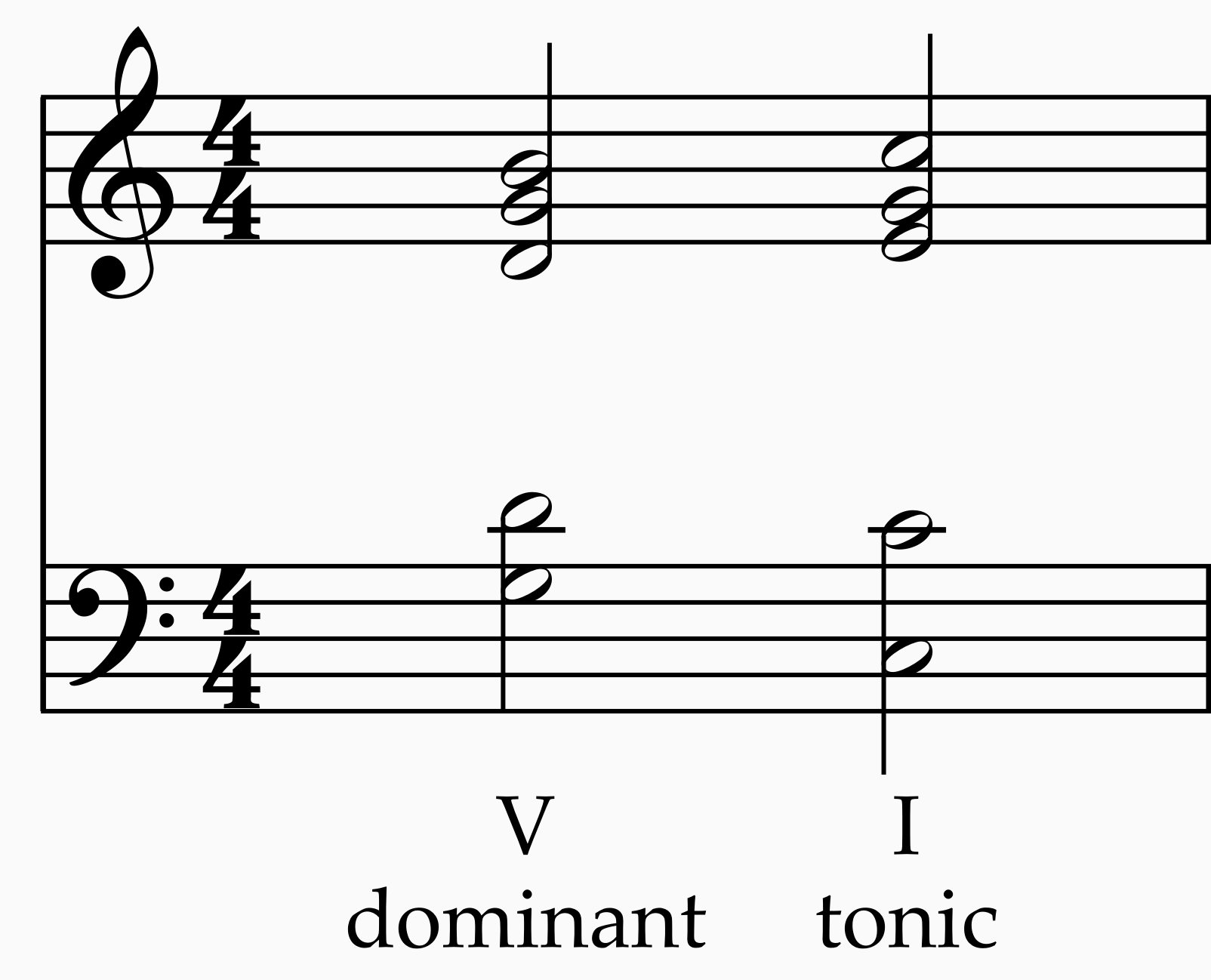

Experiencing the Chord-Connections. Let's do it together.

Figure 12. Dominant -> Tonic. The dominant chord prepares the ear for the tonic.

Figure 13. Subdominant -> Tonic. The subdominant also prepares the tonic but the preparation is more introverted because it is approaching the tonic from the lower fifth: F->C as opposed to the dominant C<-G which is more extroverted coming from the upper fifth.

The subdominant is better known to prepare the dominant. In this sense, it is known as a predominant chord.

Figure 14. The IV prepares the ear for the V. The V prepares the ear for the I. Like a falling apple, the harmony moves closer and closer to the stable ground of C major.

I encourage you to continue this research and find how each of the other triads relate to the tonic before moving on. You can use the recording that goes with Figure 11 where I go through the chords, and write down your thoughts on how the chord feels to you. Group them as either dominant, predominant or tonic. We'll be doing it together in the next section on chord progressions, but if you discover it for yourself it's best. After all, no one can write or perform your music but you. For now I'll pause the analysis with the dominants and subdominants (figures 12 and 13) as these two degrees are the most fundamental and important in all of harmony.

The Chord Progression

We've come to the progression of chords. A chord progression always seeks to achieve a goal.

The tonic is the most stable note in the scale. It is analogous to the fundamental tone in the harmonic series: all of the tones live in relation to it and strengthen it with their presence in different degrees. We've seen that the dominant chord prepares the ear for the tonic, and we've also seen that the subdominant functions to prepare the dominant and is appropriately called a predominant harmony.

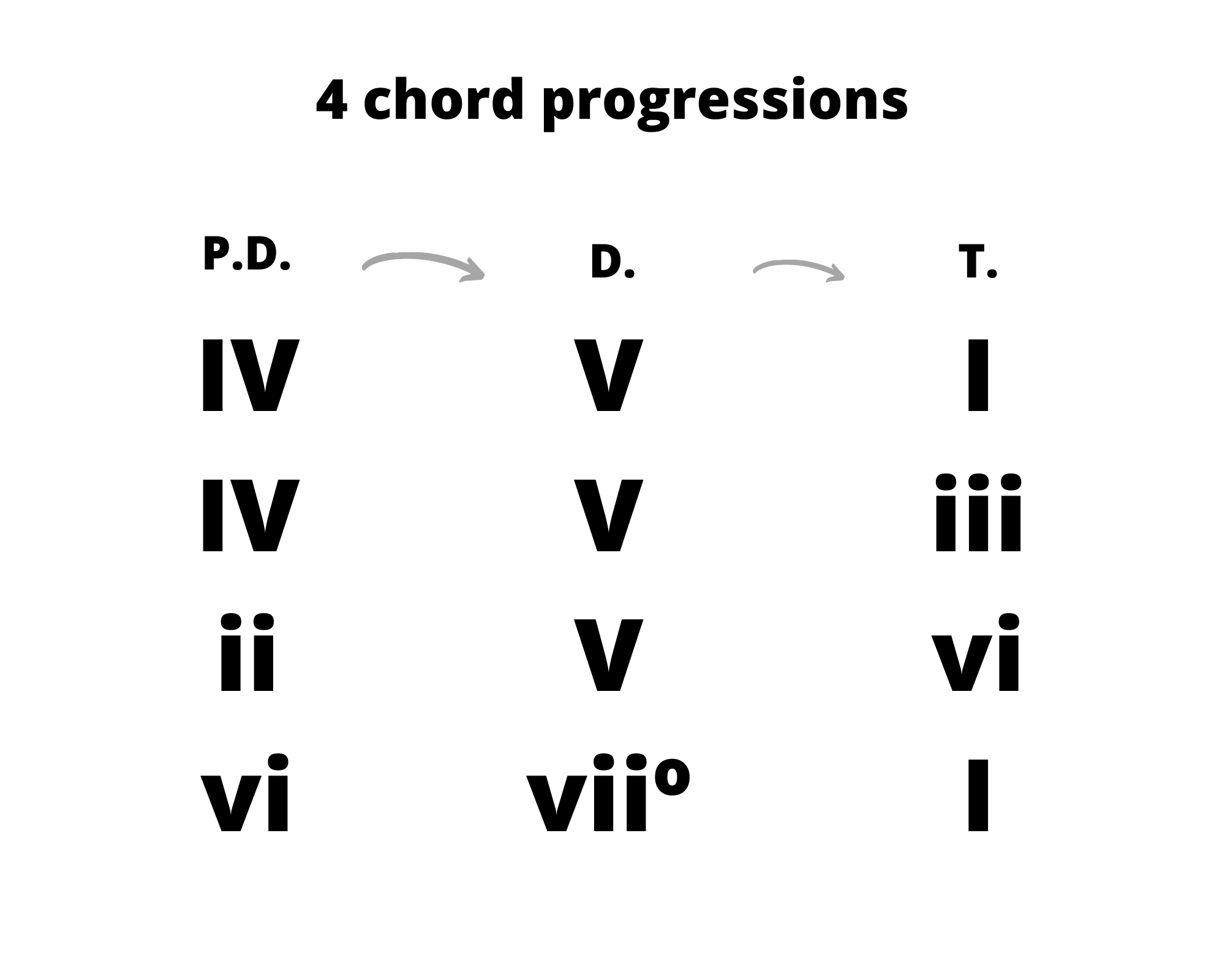

So the logic here is predominant -> dominant -> tonic. The goal then for this logic is to arrive and conclude, since the tonic is the most stable.

From your research hopefully you saw that the other diatonic triads have predominant or dominant qualities to them. Once you experience them, you can group them together into these categories and effectively show the tonics, dominants, pre-dominants, and their alternatives.

Figure 15. The diatonic tonics, dominants, pre-dominants, and their alternatives.

So now we can make several chord progressions that follow the logic of achieving a goal to establish a stable tonic.

Figure 16. Writing the chords this way of course is not musical but shows the power of thinking with chord representatives. Turning these chords into sound requires writing them down and voicing them and singing or playing them. Turning the sound into music requires phrasing.

This goal is moving toward stability. But your goal could also be to move away from stability, so starting on a tonic and ending on a dominant. The logic to achieve that goal would be tonic -> predominant -> dominant.

Figure 17.

Challenge: Write a chord progression that achieves a goal. For example, you want to establish G major as a tonic. So write a ii V I progression in G major. Or, let's say you want to move away from E major. So you would write I vi V. You can play these chords on a keyboard, or write them down with their names (C-F-G) or Roman numerals (I-IV-V) and write them in 3 or 4 voices in open position. If you've never done one before and manage to write your first one, send it in at jordan@jordanali.com.

Circle Progressions

Consider arranging the notes of a C major scale, but not with ascending seconds but descending perfect fifths, from C to C.

Figure 18.

Nice! Now we've found the bass movement for a circle progression.

Figure 19. The circle progression from C to C.

A circle progression is really common in Baroque music, but it can be found in music throughout the ages. This link actually shows some amazing examples, including the Brandenburg Concerto no. 2 which I've been playing all day since discovering this link.

In high school my teacher made us remember the phone number 473-6251. To this day it helps me out with writing smooth chord progressions. The fifths move from tonic through each triad in the diatonic scale back to the tonic again. The goal for circle progressions is to arrive at a tonic but do so in a prolonged way.

Using Chords

Chords can be arpeggiated.

Figure 20. A cool bass line from a simple progression.

How to find the chord to use during melodic harmonization.

Let's say you wish to harmonize this melody you wrote.

Figure 21.

As you can see, most of the notes here are in the D major triad: D-F#-A. So, we've got our harmony!

Figure 22. The ear is kept interested by inverting the triad.

But there is one note, the B, that is not in the D major triad. How do we harmonize B? Simply find the chord that B appears in D major.

Figure 23. The diatonic triads of D major. B, the note in blue, appears in 3 chords. You can then harmonize B with the ii chord, or the IV chord, or the vi chord.

Figure 24. Improved harmonization.

The Minor Mode

The minor scale has more notes in it, and therefore more harmonic possibilities.

Figure 25. The A minor scale and the diatonic chords in A minor. As you can see since F and G appear both natural and sharp in the scale, so every triad that has a F or G in it can come in two forms.

But the functions are still the same. That means that the logic can still be applied.

Figure 26.

Predominant -> Dominant -> Tonic

You now just have much more to choose from.

Tasks to refresh your chord writing practice

1. Write a chord progression in 4 voices. Use the voicing that I used in figure 9.

2. Revisit diagram 16 and 17 and write some chord progressions in the minor mode, using the chords in A minor from figure 25.

3. Use the chord alternatives more in your song writing. For example, use iii instead of I at some places in your songs. See what happens.

Summary

Working with chords is kind of like working in the full 3 dimensions of music, the first dimension being the tone and the second being the intervals. The jump into this dimension allows us to explore the entire world of harmonic possibility. Learn the chords by hearing them and feeling them. Practice part writing to get in touch with how the tones guide the human ear. Chord functions are really just how chords behave based on how they sound in relation to a stable sound.

In the next lessons we will learn how to use chords and harmonic tension to build all of the different types of cadences, to establish a key.