Cadences, Voice Leading, and Phrasing

On the origins of the musical cadence, and a reference guide to composing with them.

Imagine that it’s year 1550. You’re a farmer living in the Papal States (now called Italy) near the small town of Palestrina, a few miles outside of Rome. The day to day life is spent surrounded by vegetation, some animals, and a few but not too many humans, and you live a hard and (relatively) short life, and never made time to practice religion.

It was discovered that your family owes some taxes to the Pope. And so you were called in to settle the debt in person. You sell a bunch of cheese and fruits, put on your best clothes, and prepare for your first ever voyage to the Vatican City.

After a long and difficult trip, and for the first time in your life, you approach the great Cathedrals of Rome. In awe, you step inside the renovated Basilica and hear the choir singing the sacred polyphonic music that will be studied some 470 years in the future—the music of none other than Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, the Pope's composer. Is there any wonder why the church had such an influence on the world?

In music, all things relate to stability.

From tones themselves all the way up to phrases and entire movements, our ears seem to need to latch on to something so that it can breathe and take in what it has just heard and prepare for what's next. If not, we become disoriented and instinctively we shut our ears and tense up to try and block out the confusion.

Consider what happens if you hear something brand new the first time, and then listen again to that same exact structure. By simply repeating it the ear is more at home; the second time, the sound—no matter how complex—has become more stable.

In this article we're going to study how to use the intervals to guide the ear to a stable sound. Specifically we're looking at how to close a phrase, and how to create a sense of resolving musical tension. We're going to see that creating stability isn't just a matter of playing more and more calm or harmonious sounds in succession. Creating a cadence is to use carefully placed dissonances and resolve them to achieve that desired end! The ear finds a stable sound as a resolving contrast to those dissonances that come before it.

Orlando di Lasso

Orlando di Lasso (1530-94) was a composer from Mons, Belgium. He, like Palestrina and Victoria, was one of the most famous and influential composers at his time.

We're starting with a piece of his to get a sense of how he used the intervals to create moments of stability in his compositions. He came before the common practice period, and he was not working with the diatonic chords that we listened to. Instead, he was working with 2 independently moving voices. This piece is a Bicinium, a composition for only 2 voices—a great study and introduction to counterpoint.

You can download the score as a PDF here.

Figure 1.

I created this recording using my midi controller and it gives you a general (but machinelike) idea of how the piece goes.

Listening Practice.

Listen along with the score and mark with your pencil where it sounds like the phrases start and end. In every piece there are many mini openings and closings, but mark where you feel these forces are the strongest at play. Give it a few listens; if you are unfamiliar with Renaissance music it may seem odd, but the phrases will soon be clear. Listen and follow along with the score and mark it first before moving on with the lesson.

Happy listening!

🎧

Finding the Cadences

Figure 2. After listening your score should look something like this. I color coded my analysis based on how I hear the piece. Isn't it amazing that you probably hear it the same way I do, well over 400 years later. Red indicates where the phrase clearly ends for me, and blue indicates a start of a new phrase. I also indicated the intervals between the two voices at the moments where the endings feel the strongest.

Remember back to the lesson on intervals where we talked about the dimension of consonance and dissonance? Some intervals, like the octaves, fifths, fourths, thirds, and sixths are more consonant. The seconds and sevenths are the most dissonant.

Figure 3. Series 2 by Paul Hindemith.

In the Renaissance and in earlier music, the more dissonant intervals were very carefully treated. If you study the score you'll see that the dissonant intervals of seconds and sevenths really only appear in a critical spot: you guessed it.

The Cadences.

Let's analyze each cadence block by red block, starting with measure 6.

Figure 4. This is the first cadence in the piece. Study it. Lasso never jumps straight into a dissonant interval, he always smoothly approaches it. In this case, the cadence starts with a relatively consonant minor sixth. The A, a note soon to appear in a dissonance, appears first in a perfect fifth with the D. The D then smoothly glides to a Bb while the upper voice holds on to the A in suspension, creating the dissonant major seventh before finally resolving to a Major 6th (G-Bb). The two voices then approach the stable octave A in contrary motion, the bass moving down, the soprano up.

With just 2 voices, Lasso creates a sense of closing, and we just saw exactly how he does it.

The next cadence is in measure 15 and we see a similar style but this time approaching not an octave, but a unison.

Figure 5. Here the dissonant interval is a major second, and he approaches it, again, very smoothly from a more consonant minor third. The dissonant major second is resolved to a more consonant minor third. The suspended note resolves down, same as last time. Then the stable unison D is approached in contrary motion again.

Notice how he ends the phrases is on a very consonant interval such as an octave or a unison, or a fifth for the smaller phrases. Later on in musical history this changes, and we end pieces on major or minor thirds and fifths as our ears get used to that relative dissonance. What we're learning is how an almost 500 year old musical mind treated the same intervals that we still have today.

Figure 6. The last cadence in the piece is the strongest one. We are no longer developing and expanding in the piece, but we have started to return back home to the ultimate stability: the silence before the first note of the piece, the G. And so this "final" cadence approaches the G that we began with, except now it has the lower octave! Unlike before we have two dissonant intervals, a major seventh and a minor seventh operating in the same cadence. Lasso moves from the most dissonant sound of a major seventh to a slightly less dissonant sound (the minor seventh) to make the final G really feel stable. Just as before, he approaches the first dissonance of a major seventh from a consonant interval, and the note that creates the dissonance, the A, is suspended from the consonance before. He repeats this intervallic process again—repeating the seventh already gives the ear stability—through a series of suspensions resolving finally to A-F#, the penultimate interval of a major sixth. And as before, the octave is approached in contrary motion.

From these musical examples, it's clear why we use the word cadence (from the Latin for 'falling'). As we'll see the strongest cadences today use this principle of resolving dissonances to create the close. First we'll look at how cadences are defined by the common practice composers and then we'll use them to establish a tonic (anywhere).

The Ultimate List of Classical Cadences

1. Authentic Cadence

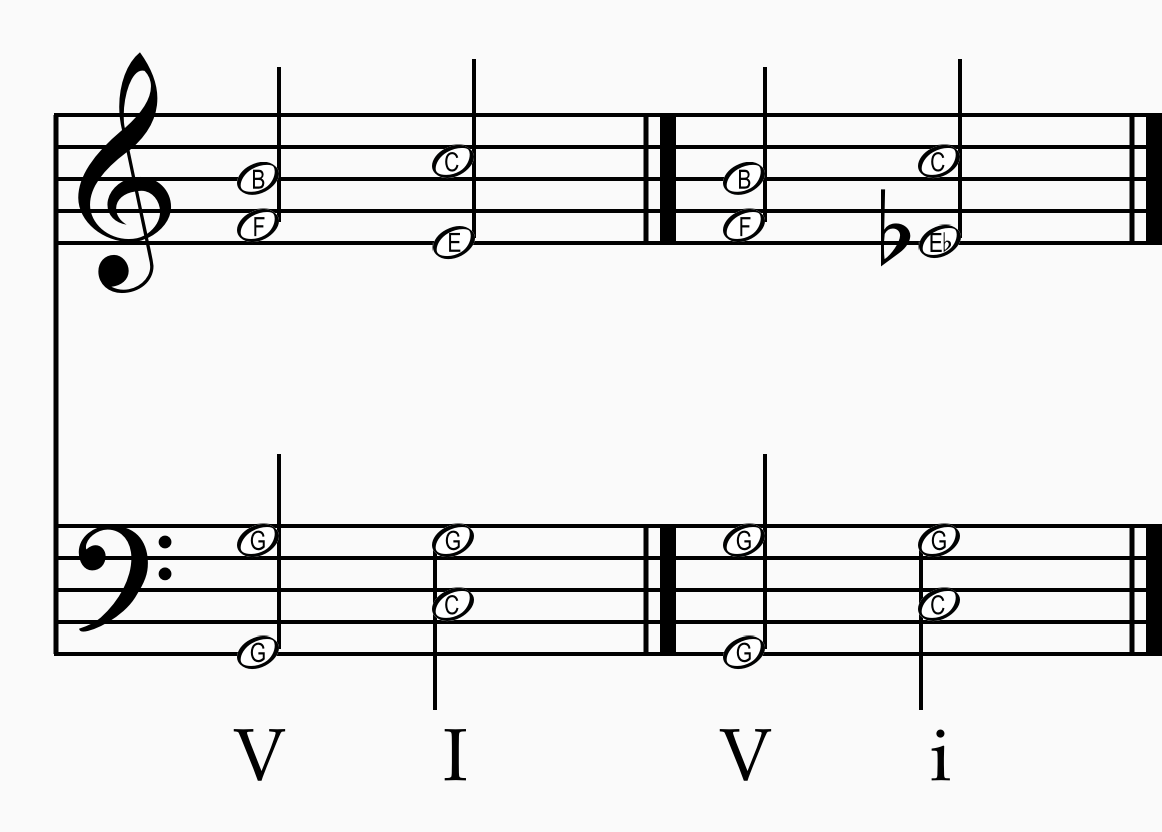

The most grand statement of tonal music: the movement from dominant (V) to tonic (I or i). The dominant chord is always the major V chord, even in minor.

Figure 7. The perfect authentic cadence. When the tonic chord is not in root position or if the soprano voice is not on the tonic pitch (if they sang the E or the G in C major) it would be considered an imperfect authentic cadence. Notice how the minor resolution is more introverted than the major. Why do you think that is?

Figure 8. There are dozens of variations of this cadence. The ii chord here can be replaced with any predominant harmony, including a tonic chord. One popular variation is done by delaying the tonic resolution as shown here by embellishing the third with notes from the dominant harmony. This embellishment was very common in the Baroque era, and you can now see how similar it is to the early music cadence.

2. Half Cadence

A cadence that ends on a dominant chord (V) is a half cadence. It can be approached by any chord including II (which functions as V/V), ii, vi, IV, and I.

Figure 9. Ending a phrase on the dominant creates this open feeling, allowing it to go on. Usually the second 'half' of the phrase ends with an authentic cadence. Notice how using the II chord makes the half cadence stronger.

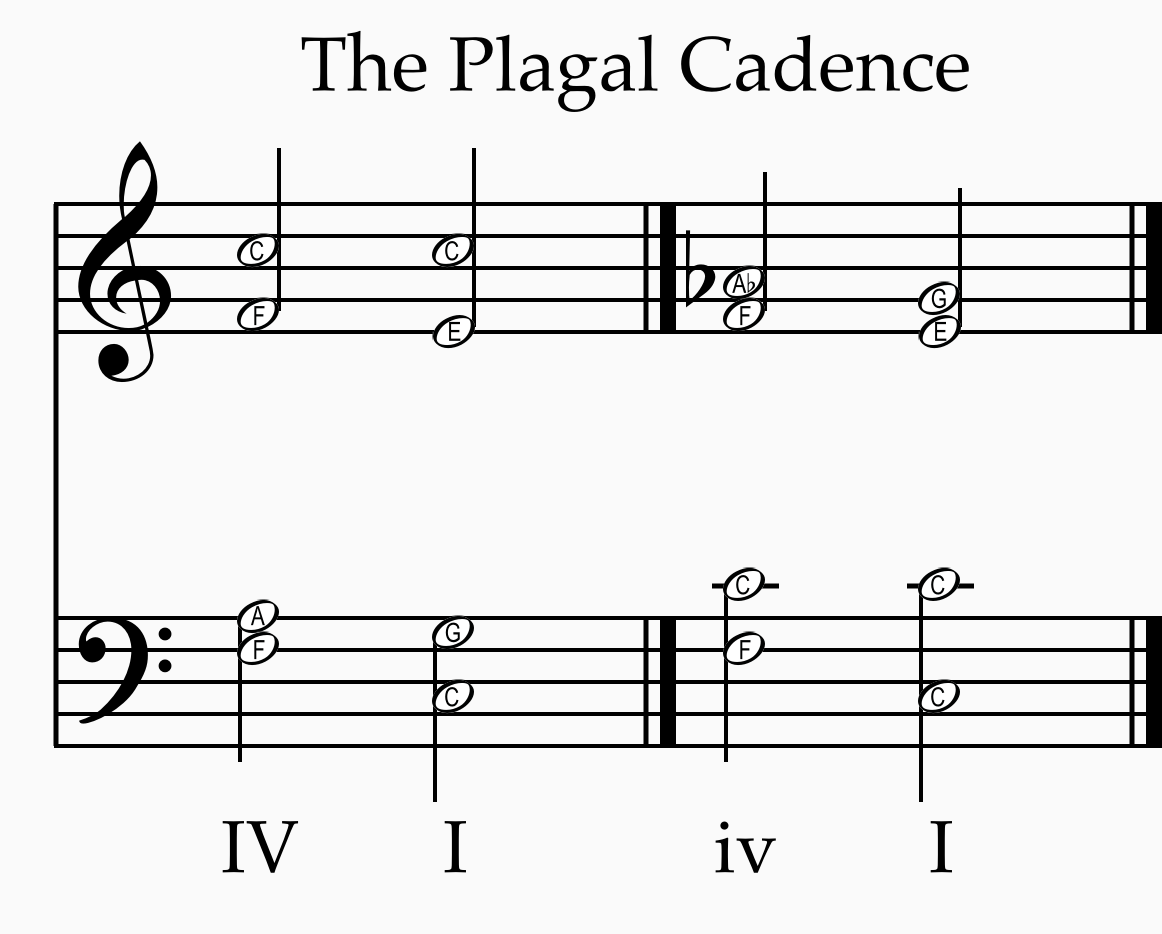

3. Plagal Cadence

A cadence that moves from the subdominant (IV) directly to the tonic (I) is a plagal cadence. A common variation is using the minor subdominant in major.

Figure 10. This popular cadence is a joy to hear, and is common to those who have sung hymns in church as the "amen" cadence. A famous use of the iv-I is the very end of the first movement of Berlioz’s Symphony Fantastique. We hear the minor subdominant has a more introverted quality.

4. Deceptive Cadence

All musicians should know how to be deceptive. When the dominant chord does not resolve to where you think it will go then you’ve been ensnared by a deceptive cadence. In major it's common to go from V to vi (a minor) instead of the tonic I chord, or V to bVI (Ab major). In minor usually it's V to VI (Ab major).

Mahler has used V to IV6 in his 9th symphony; a really unstable (and powerful) deceptive cadence. Listen at the end of the clip below.

Figure 11. As you can imagine, the deceptive cadences are really useful to quickly change keys.

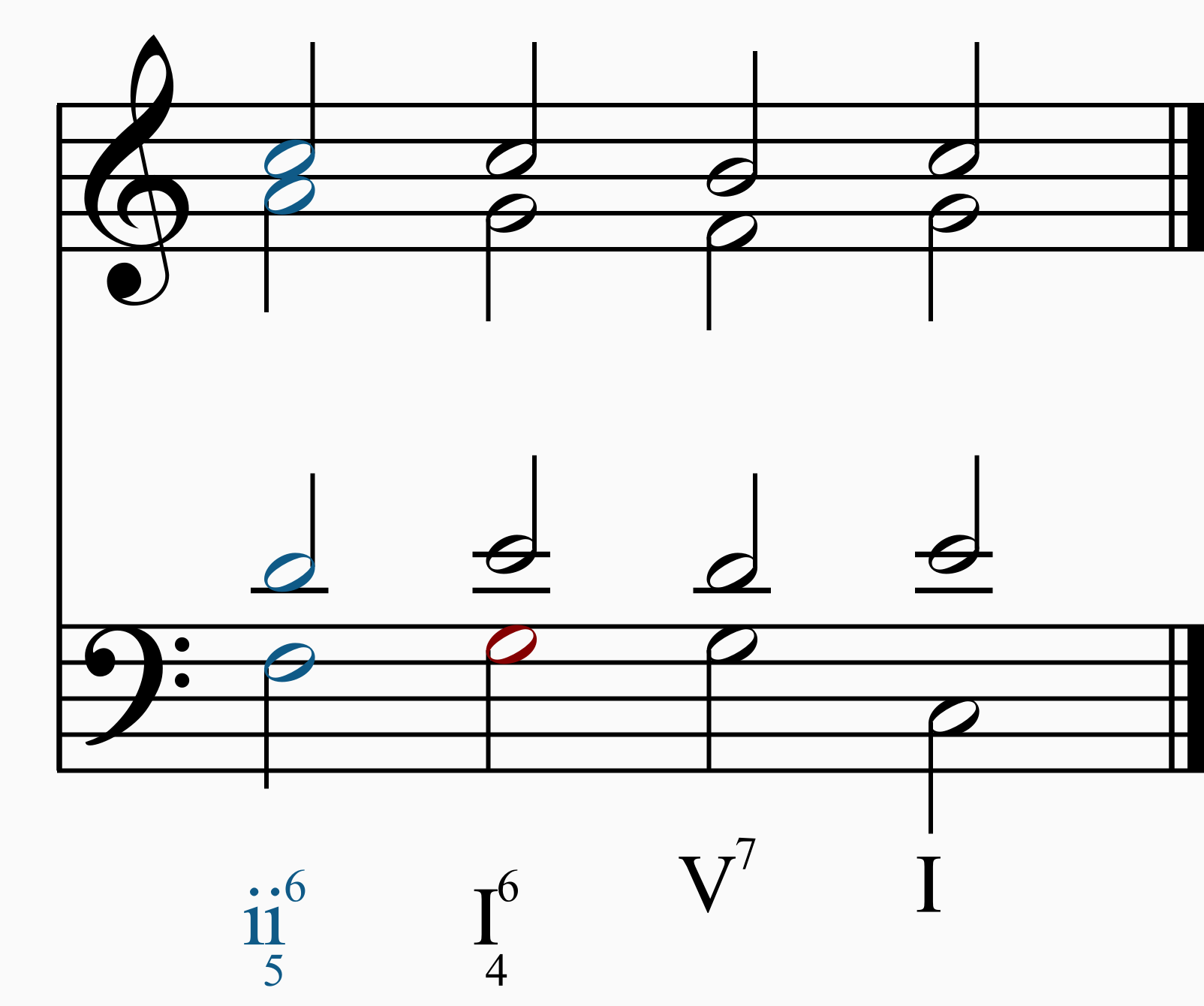

The Strongest Cadences (Final Cadences)

The final cadence usually employs the tonic 6-4 chord (second inversion) where the bass sings the fifth of the tonic. The interval of a fourth between the fifth (G) and the tonic (C) creates a dissonance that resolves down, creating that falling sense that we remember from the sound of the Renaissance.

Figure 12. The tonic 6-4 chord can be approached by any number of predominant or dominant chords, including the chromatically altered ones to create an even stronger cadence. The skeleton of this cadence is to approach the tonic with the fifth in the bass. Here is an example of chromatically approaching the fifth with German chord (a chromatic alternative of the subdominant IV chord, and can be felt as a very strong predominant chord).

Figure 13. The German chord is like a splash of color after hearing so much diatonic harmony.

The German Chord in a Final Cadence

The first measure of figure 13 tries to show how the German chord evolves as a chromatically altered ii7 chord in first inversion (labeled by the ii6-5). Notice how the ii7 chord and the German chord have exactly the same notes if you take away the accidentals. In practice though, the German chord is not smoothly approached. It's heard as a strong harmonic contrast, and so composers approach it with a jump like in measure 2.

Figure 14. (Bonus) If you're like me and didn't like writing in "Ger6" in your harmonic analysis, and wondered with burning desire what Roman numeral you can use to label it, I was once taught this approach. You can think of the German chord in this way shown by Figure 14. The German 6 is the first inversion of the "sharp minor iv with a flat 7th," written as "+iv6-b5". Nowadays you can see why I just write "Ger6".

Establishing A Tonic (Opening Cadences)

Figure 15. The most direct way to establish a tonic key is to surround it by its upper fifth (dominant) and lower fifth (subdominant). Even when we hear the ii chord, our ears hear the F in the D minor as the subdominant of C, which is why it's considered a predominant chord. When playing a cadence, always try to feel the harmonic expanse from the tonic to the subdominant, and the resolving tension from the dominant to the tonic. That is a key to phrasing.

Figure 16. A popular chord from the classical era is the Neapolitan chord, common in minor keys. It's a Major flat-2 chord. So in C minor, the ii chord is D, and so the flat ii chord is Db. The Neapolitans are major, so Db-F-Ab. Here is how it is used to establish C minor.

Finally, you can mix modes with your progressions. So instead of writing I IV V I you can write I iv V I. The iv is taken from the minor mode. Notice that it still follows the same logic of the progression, tonic-predominant-dominant-tonic, and all we’re doing is replacing a predominant chord with one from another mode.

Summary and Reflection 🤯

Before we go, and now that we've looked at the common practice cadences, let's take a look back at the Bicinium. First, remember that major and minor didn't exist back then, so it doesn't make sense to analyze it from the point of view of the common practice period. But it did come before it, and so let's see what we find.

The first note starts on G, but the harmony quickly falls to a more stable Bb, which hints at 'g minor'. That hint is confirmed by the key signature, but again he did not think of it as G minor. Now, go and look at each of the notes that Lasso cadences on.

The first cadence stabilizes on A. Then the second cadence stabilizes on D. Then the final one cadences on G. G, A, D, G.

And so, here we see the very proto-beginnings of a i ii v i cadence at play on the level of an entire piece.

Exercises

Write cadences in D minor (1 flat) and F major (1 flat). Try and use each of the cadence progressions that I mentioned here, and embellish one. Practice writing opening and closing cadences in different keys. Then most important, play them at the piano and sing each voice to get a sense of how the voices phrase.

Additionally, listen for cadences. Every tonal piece has at least one. Identify those that don’t follow the usual tonic-dominant resolution. Then in your own pieces analyze them and use that analysis to determine how they could be phrased based on tension and resolution.